A couple of centuries have passed since Nietzsche’s proclamation of the Übermensch. Who he assured us would be on the way shortly. So, where are they?

Napoleon? A shadow on an island in exile.

Ford? Disney? Fortunes left in tatters, corporations sucked into mediocrity.

Churchill? An Austrian Painter? Both ended the empires they inherited.

Trump? American arrogance that didn’t actually do anything in power.

Nietzsche’s entire Genealogy of Morals can, in a generalization, be seen as a critique of asceticism. An asceticism, for Nietzsche, exemplified by the priestly classes of Christendom and Buddhism. Those piteous, ‘unworldly’ people who make a big thing of their religiosity. Signalling virtue by their self-denial. Prayer beads, church attendance and meditation, covertly for the public perception qualities they bring.

We are promised by Nietzsche that the opposite is on the way: Surely, the opposite of meekness is a golden escalator.

We are instead infested by a continuation of the same: ‘social justice’, productive microdosers and ‘trad’ homesteaders. The power of asceticism has instead reached a fever-pitch in the attention grabbing technology.

The extreme self-realization of ecstasy, depression, intoxication and the full chemically-induced trip has been branded unsocial. In contrast to Nietzsche’s prediction, the theological monks of old has been transfigured into the productive ‘hustler’. Microdosing, sober living, meal prep, brand-building and the vengeance of the Protestant work ethic. The self-denial of contemporary times is signaled through the rejection of social media, film, music and modern conveniences. These bestow the same automatic and assumed blessing of old.

An interesting issue you can find in both Nietzsche and Schopenhauer from the contemporary perspective is their conception of Buddhism. Although understandable, given their epoch, we are met with an exaggeration of the goals of Buddhist dharma (“practice”).

Nietzsche conceives of the Buddhist ideal as one of self-denial, and thus asceticism, which is contrary to the spirit of the self-directed Übermensch. Schopenhauer, given the problem posed by the unending desire of the will, views the practices of Buddhism as an escape from such things. He conceives of enlightenment to be detaching from this world.

On the contrary, as I have begun to study Buddhism and its practices more deeply I understand the aim to be closer to balance and not self-denial or detachment. In my current view the prescriptions of Buddhist scripture has much in common with those conceived in European antiquity, particularly Aristotle and Plato.

To give an example the dharma of seated meditation doesn’t have the aim of ‘emptying your mind’ (as the popular conception unfortunately believes). But, instead has the goal of being able to experience thoughts without entering that familiar monologue that follows when we indulge our natural neuroticism. Buddhism doesn’t engage in some fantasy of empty-headedness. Instead, Buddhism acknowledges that as long as we are breathing our minds will race according to sensory conditions. Despite this, we can learn to self-direct our desires and overcome the anxiety of existing.

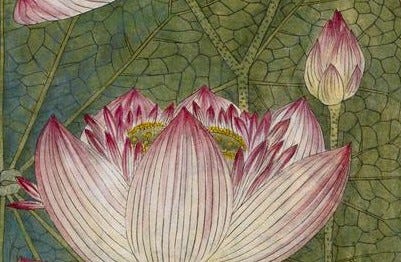

The sacral chakra (“tanjeon”) can be focused upon during meditation, allowing it to rise and mix with the fiery energy naturally blazing in the human mind. A lotus pond can be allowed to form in the base of the mouth and the human animal can aspire to become an Übermensch of balance.

Buddism = The humanist wings of Icarus. Better to collaborate with someone Outside to grow permanent wings.