The Religion of Birth

Religion, Ideology or societal ‘values’ all have basic principals at their foundations. While day-to-day practical concerns and agreements fluctuate. Every outlook has some set of axioms (philosophical immovables) which cannot be negotiated. Every expression of human will is ultimately driven by some base reason, physiological or intellectual. Such principles can be discovered underneath the messiness of human action and inaction when the question: “Why?” is asked enough times, assuming the responses are honest answers.

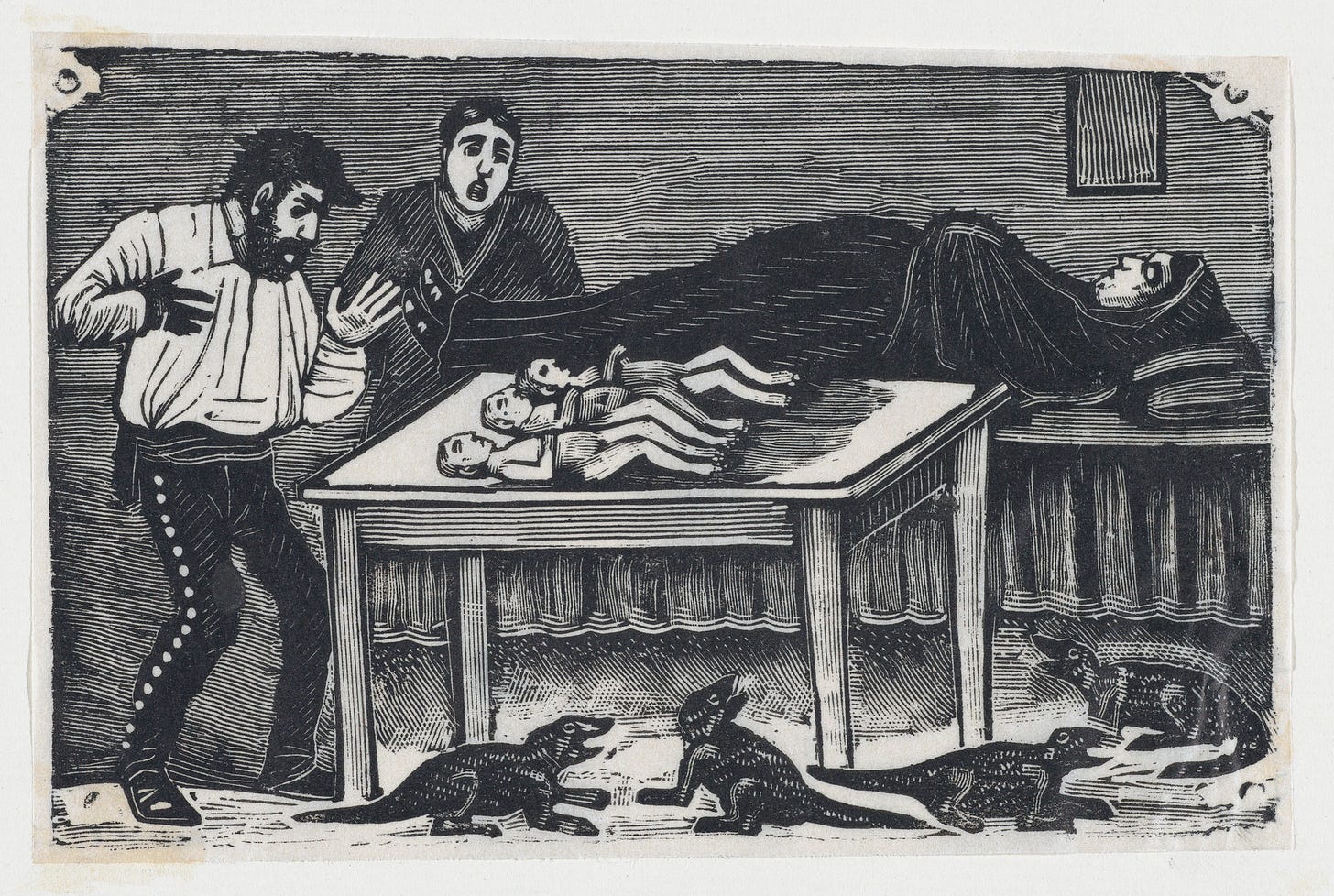

Such axioms are often, in some roundabout way, connected with death. The directness of this connection taps into our inherent fear, respect and concern in regards to eschatology. This obsession with ‘the end’ and death, naturally, concerns not only our own fate but that of the rest of humanity. It is for this reason that what we leave behind (or don’t) typically occupies those most fundamental of philosophical and political questions. This topic, understandably, evokes high emotion and violent tension.

“The interest inspired by philosophical and also religious systems has its strongest and essential point absolutely in the dogma of some future existence after death.”1

With this in mind we return to the topic of eugenics, which almost seems a prime example of such axioms with a clear connection to eschatology. It is undeniable that the “eugenic ideal” is a value which looks from beyond the individual subject and their individual life. Concerning itself not merely in the mass of humanity present in current genetic stock, but also projects its ends to the situation in generations to come. Beyond a simply material perspective, such a driving force could aspire to take up a spiritual or moral significance. Those concerned with the eugenic reality certainly make “their object the improvement of the race”, but could also profit from man’s inherent sense of eschatology. An importance over the transformation of ourselves and the final apocalyptic state man is to find himself in lies waiting to be evoked by eugenical ideals.2

This eugenical religion was exactly what the original eugenicist, Galton, proposed:

“A whole-hearted acceptance of eugenics as a national religion that is of the thorough conviction by a nation that no worthier object exists for man than the improvement of his own race;”3

You might immediately, depending on your prior convictions and temperament, either wince of affirm at such a proclamation. But, to remain level-headed it is important point out some implications which might assuage each side of the eugenics question.

Firstly, for the anti-eugenic viewpoint it is important to return to the distinction between positive eugenics and negative eugenics. Such a potent assertion in favor of eugenics on the societal and spiritual level need not involve the ritual sacrifice of those considered ‘weak’ or sacraments of castration as might be instantiated under a regime of negative eugenics. Instead, a positively eugenic spiritual-societal regime might incentivize larger families, younger marriages or dissuade technology which deprives the race of sexual potency (most obviously pornography).

On the other hand, it must be pointed out to the staunch eugenicist, who is salivating at the previous description, that such created ‘religions’ often find themselves with a God-shaped hole. Such a existentially missing piece can only be properly filled by a spiritual tradition formed over time and across multiple generations. Failing this, it is either occupied by hedonistic vapidity or neurotic action. This factor is quite ironic in the case of a eugenical religion. Furthermore, such imposed axioms on the level of a ideology or religion have historically found themselves of the facilitating end of clearly dysfunctional societies and outright cruelty. For example, The Cult of Reason in the French Revolution or the state atheism of the Soviet Union.

These concerns aside I consider this an invitation to dream. Perhaps, where we have found ideology and religion wanting we can aspire to truly improve the human race. By accepting eugenical realism this development could be conducted on the order of the constituent parts of man. Material, which in the concreteness of reality, truly drive our creation. We have learned to survive, for the most part: “Life presents itself first and foremost as a task: the task of maintaining itself”.4 Now that we have the social and technical ability to “maintain” ourselves in abundance, why don’t we start on improving ourselves?

It is exactly the propagation of life in sex and birth which gives the races of man the ability to live historically—to live beyond immediate material concerns with the future of the species and one’s own race in mind. This is the eschatological force which has always driven man to do great things. An intellectually-enabled capacity which allows us to be just, forgiving and kind. It is with eugenical reality in mind that we could sanctify the orgasm beyond pleasure, to bless sexual fluids and sexual organs at the doorstep of eternity.

“The satisfaction of the sexual impulse goes beyond the affirmation of one’s own existence that fills so short a time; it affirms life for an indefinite time beyond the death of the individual.”5

To put my point in stark terms: without an engagement with the reality of the ongoing and inescapable eugenic process we are left with a base perspective on the biological substrate. This is an outmoded and naive rejection of the importance of the reproductive process. We remain in moral stasis on eugenical reality at the peril of the species. That which projects man beyond his feeble self and metaphysically into the future is subverted if our diluted ethical sense cloaks mechanisms of such primal importance in guilt, shame and taboo. The destiny of the human race is at best retarded, at worse negated if sperm is simply a cloudy fluid, eggs merely fungible receptacles and fetuses just clumps of transient cells.

“Yesterday sperm: tomorrow a mummy or ashes.”6

Schopenhauer, A. (1966). The World as Will and Representation, Volume II. Translated by Payne, E.F.J. New York: Dover Publications. p.161

Schuster, E. (1912). Eugenics. London & Glasgow: Collins’ Clear Type Press. p.23-24

Galton, F. (1906). Eugenics. Sociological Papers Vol II, The Sociological Society. New York: Macmillan. p.1

Schopenhauer, A. (2014). Essays and Aphorisms. Translated by Hollingdale, R.J. London: Penguin Classics. p.53 On the Vanity of Existence.

Schopenhauer, A. (1966). The World as Will and Representation, Volume I. Translated by Payne, E.F.J. New York: Dover Publications. p.328

Aurelius, M. (2014). Meditations. Translated by Hammond, M. and Clay, D. London: Penguin Classics. p.32